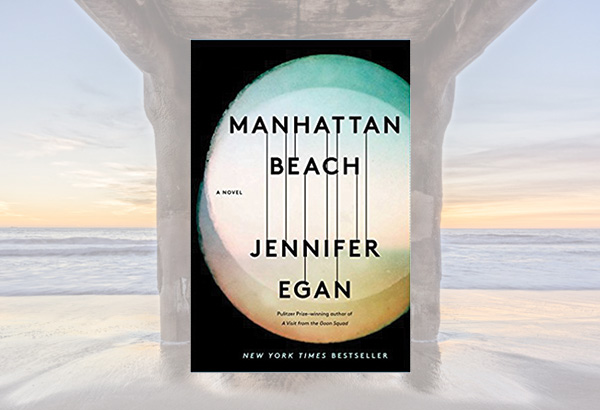

I was pleased to see the novel Manhattan Beach included in Sandy Dominy’s recent “Books You Should Read Now” in Prime Women. It’s been on many other lists of notable books as well, so when I received it for Christmas I was eager to give Manhattan Beach a go. I hadn’t read author Jennifer Egan’s previous works, but I was soon convinced she is a thoughtful craftsperson worth following. She’s undertaken extensive research for this novel in order to recreate a world in all its fullness: War (WWII) and Crime (the Mob) and the City (New York) and Families (here, with a suddenly absent father) along with the universal need to just get on with it, all intertwined as they would have been in real life, without the awkward anachronisms of intentional cultural references.

We see the world as these characters do, with the culture’s assumptions such as how a “lady” should act accepted more or less whole-cloth by those within it. When a troubled teenaged Anna, the protagonist, compulsively seeks physical pleasure, she accepts the resulting shame and secretiveness as necessary, too busy living her life to stop to argue with herself or others. When she decides she wants to become a diver as part of the war effort, it does not seem to be because the character or the author is trying to make any point about women’s equality, but because Anna, for several reasons, wants the job, and justifying herself to others comes not through any philosophical or political statements but by doing her job well. Despite this apparently unselfconscious view of the character’s world, she does carry a powerful implicit philosophy with her: an aware observer, she may evaluate others, but she does not condemn them.

I might designate this novel as a slow page-turner. We want to know what’s happened and what will happen, but along the way we pause often at the gorgeous use of language, at poetic descriptions such as Anna’s revelations that with diving, “A burst of pleasure broke inside her. This was like flying, like magic—like being inside a dream” and “She took a long breath and shut her eyes and immediately felt a new responsiveness in her fingertips, as if they’d suddenly awakened from sleep.” Earlier, Anna’s sister gazing at the sea wordlessly becomes “a mythical creature whose invocations could summon storms and winged gods, her blue eyes fixed on eternity.”

Egan masterfully supplies subtle twists to characters and perspectives that we haven’t seen coming, such as the many motivations of debonair mobster Dexter and the nearly mythic journey of Eddie, Anna’s father. Toward the end of the book, Egan shows her sleight of hand in dissolving barriers of time and self in a scene in which one of these character’s death slides seamlessly into the earlier rebirth of the other. With this, everything we know as readers is changed, but the dramatic shift in turn blends easily into the utterly realistic and timeless revelations of a girl growing into a young woman, incrementally seeing everything around her in a new light while simultaneously struggling to realize her place in the world.

The character of Anna is so lovingly, carefully drawn that I was occasionally disappointed by the characters we aren’t allowed to know. Anna’s aunt, Brianne, is a foil to her mother who offers them both a glimpse of a more independent, perhaps one might say liberated, way of living in the world. We find out she is not everything she seems, but that is hardly a surprise, and we never see much of her inner life. Nor do we know much about Agnes, Anna’s mother, who drops off the charts rather early on—something that happens in real life often enough, but she becomes so ghostlike that we are left wondering what we don’t know about Anna, as well. Dexter is always a cipher, a compelling and sympathetic one despite his considerable sins, but like an indifferent actor he sometimes seems strangely removed from agency in his own life. Everyone’s stars are crossed, and we are called to observe their fates without a lot of passion.

Egan achieves her most lovely characterizations by showing everyone’s relationship with Anna’s sister Lydia. Severely disabled but physically beautiful, Lydia is certainly some sort of symbol for the tragic society that stands on manners and appearances while the cogs underneath are corrupted and casually murderous of innocent and guilty alike. But the depiction seems real, not forced into a metaphor. The ambivalent feelings, the devotion, the physical demands, and the persistent, far-reaching ties that each family member, and a few from without their sphere, experience and demonstrate in relation to Lydia are true to what I know of real families and their dependents. Only in the brief, aching moments when Lydia experiences the sea do we get a glimpse of her own experience, and with it of all the conceivable futures that have been thwarted.

The ending of Manhattan Beach, for all its revelations and relocations, does not tidily wrap everything up. In the coming fog we see the potential for boundaries and assumptions to shift again. Anna has yet to find out just what sort of person the man with whom she’s liaised herself was, and neither is her father’s lasting impact conclusively defined. What we are left with are a true richness of experiences and a better understanding of all the possibilities.