The holidays bring families together and along with holiday cheer comes a host of old relationship dynamics. I am the youngest of three children. Growing up with a single mom, I was often fighting for attention. As an adult, that same child-like frustration arises when I am not being heard. An emotional trigger is any situation that invokes old psychological injuries. So, you can imagine how my house full of family at the holidays might trigger old feelings of frustration.

Fortunately for all of us, there are ways to disarm our emotional triggers. Engaging our mind, body, and emotions, we can achieve what Christopher Bergland calls grace under pressure. A world-class endurance athlete, Bergland applies his sports training to combat distress in everyday life. To understand how, let’s first look at how emotional triggers work.

Three major players in the brain contribute to an emotional trigger. They also hold the keys to disarming it.

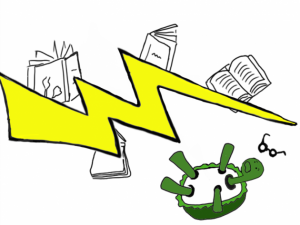

Foremost is the amygdala. One could say that the amygdala is our brain’s superhero, if that superhero were lightning fast and well intentioned but not very bright. Sometimes called the emotional center, it detects any potential threats and prompts our protective reactions, like fight-or-flight.

The second player is the prefrontal cortex, otherwise known as the thinking center (for good reason). It has the hefty task of making sense of all sensory input – sights, sounds, smells, and feelings – that we encounter.

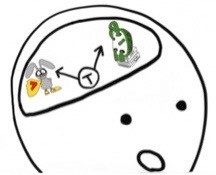

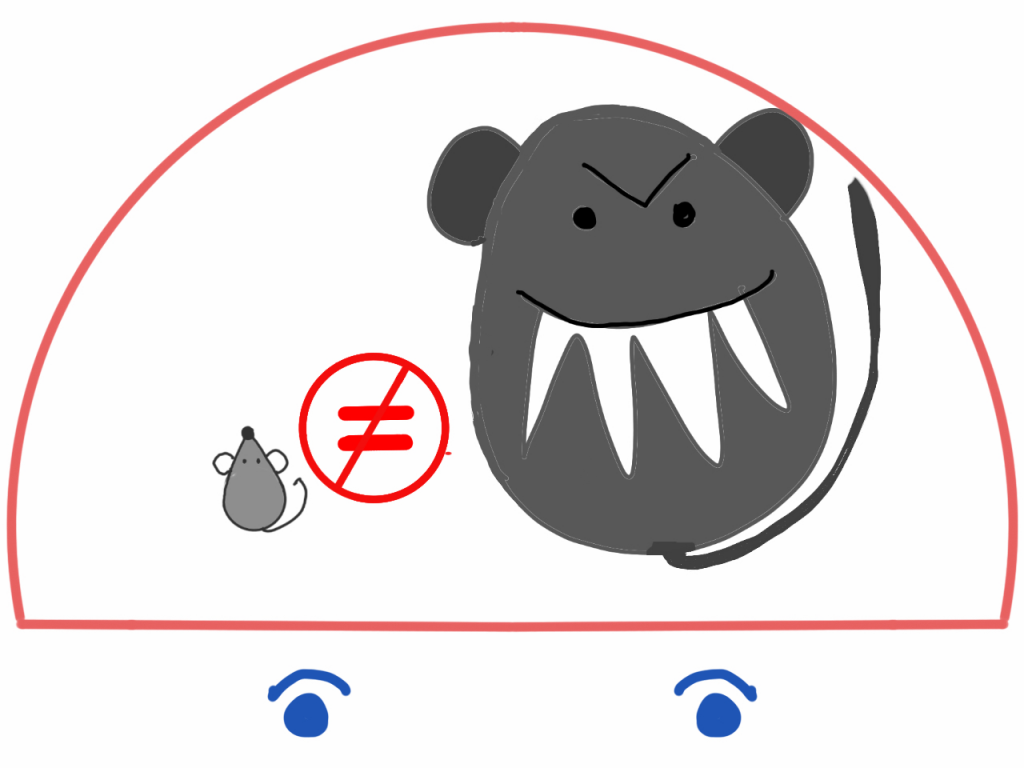

We can be emotionally triggered when something unexpected yet familiar happens (stumbling upon a mouse, for example). Sensory input travels both to our thinking center (the prefrontal cortex) and our emotional center (the amygdala).

Our amygdala then recalls past sensory input (like how scared we were when a mouse ran across our pillow) while our prefrontal cortex searches for relevant meaning and context (for example, mice aren’t normally dangerous, and it was more scared of us than we were of it).

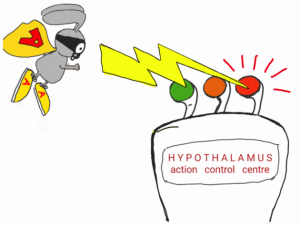

The amygdala jumps into action using the third player, the hypothalamus (or the action control center),to release stress hormones and trigger a fight-or-flight response. Not only is the amygdala faster than the prefrontal cortex, it actually blocks the thinking center in order to save time. Emotional Intelligence author Daniel Goleman calls this block an amygdala hijack.

By the time the thinking center catches up, our protective responses are already in action. The amygdala hijack is designed to (and sometimes does) save our life. Other times, it triggers defensive emotional reactions that we might not want nor choose.

When we are emotionally triggered, we feel vulnerable. As a result, we use defenses that protect us against further negative feelings. We evade negative feelings by avoiding, numbing ourselves, or fighting back.

Sometimes refocusing on the wine, pumpkin pie, and football is the perfect antidote. This post doesn’t disparage such defense strategies; it aims to give us the choice to use them rather than be hijacked by them.

Disarming Emotional Triggers

Our negative emotions help us. Sadness prompts us to retreat and heal, anger gives us courage to defend our boundaries, and fear alerts us to protect. Ask if your triggered emotion is helping or hindering you. If your answer is the latter, take these steps.

1. Reengage the thinking center.

Even a subtle emotional trigger can hijack our critical thinking. Whether or not we are consciously aware of it, a trigger can make us feel the way that we felt the first time we were emotionally injured. Though it feels like that painful time, it is not that painful time. We can demonstrate to our amygdala that we are not in danger right now by using a thought diary.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy’s master tool, the thought diary, asks you to write down the triggering event and express your thoughts and feelings about it. Then it helps you test whether thinking this way is realistic and helpful and, if not, how you can reframe your thinking to disarm the trigger. With MoodTools Thought Diary app, you can do it all from your phone.

2. Redirect the emotional center.

Practice compassion toward yourself and others. Compassion may sound simple but can be very difficult in a triggering moment. Getting upset or pulled back into old family patterns can lead us to beat ourselves up or blame others for upsetting us.

If you can say to yourself, ‘I understand why I (or you) act and feel this way. I prefer it to be different but it’s not. And that is okay’ and actually believe it, great! Just recite it to yourself when you first feel your body tensing up. It only works if you believe it, so you may need to work on manifesting compassion before the holidays.

The Self-compassion Skills Workbook by Tim Desmond guides you through a 14-day program with meditations that are specific to your current mood. Developing self-compassion skills not only enables us to accept our own humanity, it better equips us to accept the fallibilities of others.

3. Use the action control center.

We can trigger fight-or-flight responses but we can also trigger relaxation responses. Diaphragmatic breathing communicates to our action control center that it is time to rest-and-digest or to tend-and-befriend (both very handy during the holidays!). Bergland suggests that any form of deep slow diaphragmatic breathing can relieve tension or frustration and get our cognitive processes back online.

Though these strategies will work the first time you use them, practice makes them work faster and more effectively. Our emotions are swifter than our thoughts and it is harder to calm ourselves once a protective response is triggered. But we can catch the fight-or-flight urge early by paying attention to the physical signs that lead up to it – forgetting to breath, tense jaw, and tightening shoulders, for example. Bergland has compiled a ‘survival guide’ to combat fight-or-flight urges that is worth checking out. Here’s to a happy and graceful holiday season!

References:

Illustrations by Dr. Jena Field.

Christopher Bergland. (2017). Vagus nerve survival guide combat fight-or-flight urges.

Christopher Bergland. (2013). The Neurobiology of Grace Under Pressure.

Daniel Collerton. (2016). Psychotherapy and brain plasticity. Frontiers in Psychology.

Daniel Goleman. (1996). Emotional Intelligence.

Rick Hanson. (2013). Hardwiring Happiness. The New Brain Science of Contentment, Calm and Confidence.

Hasse Karlsson. (2011). How Psychotherapy Changes the Brain. Psychiatric Times.

Joseph LeDoux. (1996). The Emotional Brain.

Joseph LeDoux. (2012). Rethinking the emotional brain. Neuron.

Joseph LeDoux. (2014). Coming to terms with fear. PNAS.

Joseph LeDoux. (2015). Feelings: What are they and how does the brain make them? Daedalus.

Joseph LeDoux. (2015). Anxious: Using the Brain to Understand and Treat Fear and Anxiety.

Karla McLaren. (2013). The Art of Empathy: A Complete Guide to Life’s Most Essential Skill.

Catherine Pittman & Elizabeth Karle. (2015). Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and Worry.

Robert Plutchik. (1980). Theories of Emotion (Volume 1).

Dan Siegel. (2010). Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation.

Bessel van der Kolk. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma.

Neil Schneiderman, Gail Ironson, & Scott D. Siegel. (2005). Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annual review of clinical psychology

Michael W. Otto & Jasper A.J. Smits. (2011). Exercise for Mood and Anxiety, Proven Strategies for Overcoming Depression and Enhancing Well-Being.

Bessel van der Kolk. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma.